One of the key steps on my growing journey was learning how to make good compost in sufficient quantity to regenerate the soil and maintain fertility from one season to the next. My compost pile, let’s call it Compost Pile 1.0, was typical of many that I see in local gardens and allotments; a straggly pile of slowly decomposing garden waste which seemed to take for ever to break down. I quickly realised that I was going to need to find a better way to make compost or face buying a lot in from elsewhere.

But what is compost? The “compost” you find in a typical garden centre is not really compost but rather a growing medium which contains some form of organic matter with added nutrients (either chemical or organic in origin). Compost is something rather different. In addition to organic matter and essential nutrients a good compost also contains a host of soil biology which is essential for establishing healthy soil which, in turn, leads to healthy plants. See my earlier article on the Secrets of Healthy Soil.

Compost is a mixture of ingredients used as plant fertilizer and to improve soil’s physical, chemical, and biological properties. It is commonly prepared by decomposing plant and food waste, recycling organic materials, and manure.

Wikipedia definition – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compost

Not all composts are the same and the kind of compost you choose to make (and use) will depend on the type of plants you want to grow. Different kinds of plants require a different balance of nutrients and, in the case of nitrogen, different forms (nitrate vs ammonium). The soil biology that is present has a big influence on the availability of nutrients, with bacterial dominant alkaline soils favouring nitrate loving plants (salads, greens etc.) and fungal dominant acidic soils favouring ammonium loving plants (fruit bushes, trees etc.) – See Box 1 for more details.

Box 1

The diagram shows the succession from bacterial dominant marginal land to fungal dominant old forest. As the soil shifts from bacterial dominant, through balanced, to fungal dominant so does the pH (from alkaline to acidic) and the primary nitrogen source changes from nitrate to ammonium.

Most soils have at least some fungi present which are essential for the cycling of other key elements, such as phosphorus, and the breakdown of carbon rich plant matter which is high in cellulose and woody lignin.

Leafy crops thrive in soils which are more bacterial dominant. However other crops which produce, roots, seeds, or fruits require an increasing level of fungal activity to attain good plant health and ensure good crop yields.

The “ingredients” and method used to make compost will influence the make-up of the soil biology and the nutrient balance of the end result. I like to think of it as being a bit like making a cake, with some composts being light like a sponge and others being heavier like a rich fruit cake.

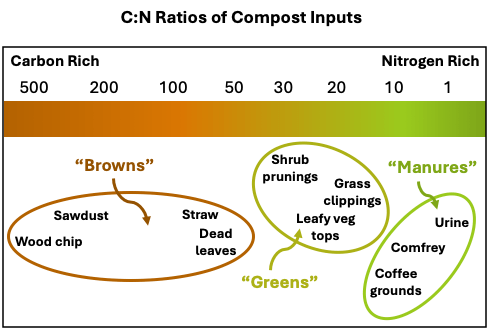

In all cases a good compost requires a roughly equal mix of “browns”, “greens” and “manures” along with sufficient water to keep it moist and enough air to ensure the right microbes as encouraged and the compost does not become smelly. Bacteria mainly decompose the more nitrogen rich manures and greens whilst Fungi are needed break down the tougher more carbon rich browns – See Box 2 for more details on compost inputs.

Just like with cake baking the “cooking” time for composts also varies with a light bacterial rich compost being ready in about a month, a more balanced bacterial/fungal compost being mature in 3 months and a heavier more fungal dominant compost taking a year or more to mature.

Box 2

A rule of thumb is to use roughly a third browns, a third greens and a third manures to create a well-balanced compost aiming for a C:N ratio in the range of 25-30. The diagram shows the carbon to nitrogen ratios (C:N) of various common compost inputs. A set of online compost calculators are also available to help with deciding on the exact proportions to use – these are particularly useful if you are composting at scale.

There are a variety of methods for making compost (see list below). All of them share some basic principles:

- inputs should be roughly chopped

- browns should ideally be pre-soaked in rainwater to ensure there are no dry pockets

- inputs should be added as a mixture or in alternating layers (brown, manure, green, brown etc.) a few centimetres deep.

- the final moisture level should be about 80% (a drop of moisture comes out if you squeeze a handful)

- the pile should not be allowed to dry out or become waterlogged over time.

Some additional composting approaches are listed here.

- Hot Compost – rapid method generally results in a bacterial dominant compost

- Mouldering or Slow Compost – resulting compost can be bacterial dominant, balanced, or more fungal depending on the inputs used and maturing time

- Johnson-Su – combines hot composting with a longer maturing phase that results in a more balanced compost

- Vermicompost (worm composting) – bacterial dominant compost, very nutrient rich

- Bokashi – special anaerobic pre-composting method useful for processing food and kitchen scraps

For more information on these head to the resources section on the growing better page of my website.

For certain composting methods there are additional things to consider. If you want to make a hot compost you will need to ensure your pile is at least 1m3 otherwise it won’t get hot enough. As you require a lot of material all in one go, this type of compost is often best prepared towards the end of the growing season. I will talk about this approach in more depth in a subsequent article.

The simplest option is to make a mouldering/slow compost pile which you can add to gradually, but you will still need to pay attention to what you add. Some of the common errors with slow composting are not chopping up the inputs sufficiently, not paying attention to the balance and layering of inputs (brown, manure, green), not adding sufficient moisture or allowing the pile to get too waterlogged. Covering the pile to retain moisture and avoid waterlogging is useful and this also ensures that the pile is shaded; microbes don’t like sunlight.

Not paying attention to these aspects tends to result in piles that are very slow to break down just like the Compost 1.0 pile featured at the start of this article. It is also best if the mouldering pile is turned a couple of times as it matures to ensure it is kept well aerated. Having 3 “bins” roughly 1m3 in size, next to each other so you can turn from one to the next and always have compost at varying stages of maturity is ideal.

Having access to the right kind of compost is key but how much of it do we need? As with everything else the answer is – it depends. If your soil is very depleted or you are creating a new bed, then you will need quite a bit. However, if you are just looking to top up a bed to maintain fertility then you will need less. As a general guide the advice from Charles and Perrine in Living with the Earth (vol 1 p. 250) suggests the following:

- If you are starting a new raised bed – apply ~10cm depth, ~50kg per square metre

- For early bed maintenance – 2-3 cm depth, 10-15 kg per sqm; at each rotation [i.e. 2 x per year]

- For established bed maintenance it depends on whether transplanting or direct sowing. If transplanting use more mulch and less compost except for heavy crops such as brassicas where compost is needed. If direct sowing treat as for an early bed because the soil will be without mulch for a few weeks prior to and after sowing

Of course, compost is only one of the tools available to us to help build and maintain soil fertility. Mulches, compost extracts and teas and other types of bio-amendment also have a role to play. I will cover these in more depth in subsequent articles.

For now – happy composting!