In some of my earlier posts on healthy soil and composts I have alluded to the use of compost extracts, teas and other garden amendments but what are they and when are they useful?

When I first started on my path to regenerating my soil and growing healthier plants I found the literature on the topic of garden amendments quite confusing. There seemed to be so many options of things to make or buy and conflicting information about their potential benefits. Over time and quite a bit of research and experimentation I have come to realise a few things which I would like to share with you here. For the sake of simplicity I will refer to compost extracts, teas and other preparations collectively as amendments.

Before I go into any detail on which amendments are useful and which are not, I feel it useful to discuss briefly why we might want to use them at all – do we need anything more than good compost? When we have healthy soils and are only needing to add compost to replenish soil nutrients used up by the previous crop then I would argue we probably don’t need extra amendments, but since most of us or a journey towards healthy soil there are situations in which amendments can give a valuable boost to our plants and soils.

Many soils are deficient in key minerals which plants need for healthy growth and, critically, they lack a healthy population of soil food web biology which is essential for establishing a healthy plant microbiome. In the early years of soil regeneration the judicious use of appropriate amendments can help us to produce healthier plants which in turn, when we compost their residues, can lead to the generation of healthier soils in subsequent seasons. Thus, amendments are a useful way of rapidly addressing chemical nutrient and plant biology imbalances allowing us to kick start our soil regeneration.

Ahead of discussing what I would term useful amendments I would like to briefly mention some amendments that are not useful, or even desirable (and why).

Undesirable amendments – typically high in chemical nutrients but possessing undesirable biology.

- Liquids which leach out from the bottom of compost piles or worm bins. I see a lot of references to this and I would warn against their use. Whilst they may contain useful plant nutrients they are typically unpleasant smelling which means they have been formed under anaerobic conditions in which many pathogenic bacteria thrive and thus are not a source of desirable plant biology. [As a side note – if you are keen on making high quality worm compost (which does not produce any leachate) then you might want to check out Rhonda Sherman’s guide]

- Compost left to steep in water for a few days, unaerated and then filtered and used to water plants – this is sometimes referred to as compost tea. Again the same issues as for compost leachate apply – anaerobic conditions foster the growth of undesirable microbes. There are better ways to make compost teas, we will come back to this later.

- Preparations of plant matter which are left in water for a number of days or weeks. This seems to be a common way of making “fertiliser” preparations from plants such as nettles or for decomposing roots of plants like couch grass or bind weed. Whilst these methods are effective at extracting valuable nutrients they again suffer from the same problem of introducing undesirable biology which is signified by the extremely unpleasant smell produced by such concoctions! Again there are better ways to utilise such plants as nutrient sources, I will touch on these later on.

Like me, I expect you have used some of the above amendments. Why wouldn’t you – you see recommendations for them everywhere! The reasoning most people offer for their use is that they work. After a fashion they do, mostly because of the high chemical nutrient levels they possess. But the effects are often short lived and the risks of introducing undesirable (pathogenic, disease causing) microbes outweighs any benefits to their use in my opinion.

So what should we do instead? The answer depends on what the soil or plants need – what are they deficient in? This could be either chemical nutrients (i.e. key minerals) or biology (i.e. imbalanced soil food web populations). You can determine what is missing by observing your plants/soils or by directly testing them. Lets take each case in turn.

Nutrient deficiencies can be apparent from observing the leaves and shoots of your plants which will show fairly characteristic problems if for example there are low levels of nitrogen, phosphorous, iron, magnesium, calcium etc. The lack of other key minerals such as sulfur, boron, manganese etc. can be harder to spot but equally important.

To better understand your soil chemistry it is a good idea to send off a sample to be tested, there are some labs that will test samples from small growers and gardeners at a very reasonable price. Once you have an idea of any imbalances in your soil nutrient/mineral levels then you can look to address this by adding appropriate amendments many of which you can prepare yourself from cheap and readily available sources.

I don’t want to go into a lot of detail on the preparation of nutrient amendments here – this could be an article all of its own. I will just describe a couple that I have used to good effect and point you towards further sources of information.

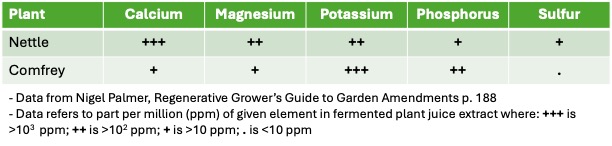

Both nettles and comfrey are a good source of mineral nutrients – see the table below for a summary. You can of course add these to your compost pile to enrich the compost that you make but if you want a more immediate source of mineral supplements to address deficiencies in your plants and soil then you can make an extract called fermented plant juice (FPJ) which will be shelf stable for up to a year and (if made correctly) will not smell unpleasant.

The secret to making FPJ is to use a lot of sugar which acts to extract moisture from the plant material and dehydrate any microbes so that they go dormant rather than multiplying. The result is a rich, dark liquid which smells strongly of the plant you extracted; in the case of nettle and comfrey is a distinctive rich earthy smell. You can find out how to make FPJ (and other related Korean Natural Farming – KNF – approaches) by clicking on the links here – Nigel Palmer FPJ prep – https://www.biomei.solutions/resources

I tend to make a fresh batch of FPJ in the late spring using either nettles from the end of my garden or the comfrey which I cultivate next to my compost heaps. Once its ready to use it can be diluted (approx. 500-1000 fold) in rain water and added to plants either as a soil soak or sprayed onto leaves to give a more immediate mineral boost. Its always a good idea to do a sniff check before you use it, especially if you’ve stored it for a while. If it smells musty, rotten or chemical (like alcohol or nail polish remover) then don’t use it at will not do your plants any good – you can recycle it into your compost heap and make a new batch.

I have used these simple extracts to good effect for the past couple of years particularly to address issues with mineral deficiencies in my fruit bushes and to help young plants build resilience towards attack from aphids and other insects. As my initial soil test results (see earlier) identified a slight sulfur deficiency I have also found nettle FPJ to be a good supplement to feed my brassicas and alliums with.

Soil biology imbalances are not as complex to address as they might seem. After all if you are making good quality compost under aerobic conditions you are already on the road to doing this. So what biological amendments can you readily make and when would you use them? This is a huge topic so I will focus on the approaches I have been using thus far and point you to further options at the end of our discussion.

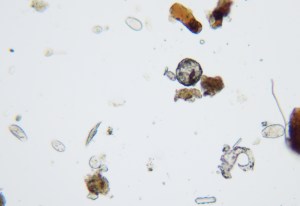

Again the best way to know what your soil is missing is to analyse some samples, in this case using a microscope. Thanks to excellent tuition from Eddie at Rhizophyllia I learned to do this myself, at least to a level which gives me a qualitative guide. If you feel this is beyond you, then again there are places which will test the soil biology for you.

If soil analysis is not an option for you then fear not! There are some simple signs of what could be missing based on things you can observe about your soil and plants, I will allude to these in the discussion below.

Compost Extract – biology amendment with several potential uses.

- Add to mulches to aid their break down – symptom to be addressed – so called constipated soils which have a lot of undecomposed organic matter on or near the surface. These tend to be high in bacteria but not much other biology and thus can’t break down organic matter in the soil very effectively.

- Inoculate seeds or the roots of transplants – symptom to be addressed – seedlings and young plants are weak with poor root systems and vulnerable to attack from pests (e.g slugs, aphids)

Compost extracts are very simple to prepare and use. All you need is some good quality compost and some rain water, a small bucket, funnel and some filter mesh (typically I use 100 micron brewing mesh). Ideally the compost has been analysed to ensure that it contains a good level of soil food web biology but if you cant do that then use your nose; if it smells in any way unpleasant then don’t use it!

This season I chose to use some of the hot compost that I prepared in the spring as it was rich in soil food web members – see my earlier compost diary post on this topic.

Here is a quick recipe which provides about a litre of compost extract.

- Place 1 litre of rainwater in a small bucket

- Add approx. 100g of good quality compost

- Stir gently and allow to stand for about 30 mins then stir again

- Filter through mesh into a clean container

- Dilute roughly 10 fold before use (e.g. 1 litre of extract in 10 litres of rain water to be applied using a watering can)

Summing up key points

- Amendments can be useful to address deficiencies in poor soils at the start of your regenerative journey.

- Pay attention to both mineral nutrients and soil biology – your plants need both

- Be careful about using amendments that may come from anaerobic processes – don’t use it if it smells bad!

The final class of amendment which deserves a mention is Actively Aerated Compost Tea which can be used as a soil soak and/or foliar spray to further enhance the health of soils and plants. Making good quality aerated composted teas is something of an art and I have yet to fully get to grips with approach. I plan to do some more in-depth experiments in the coming season and will be sure to share my results in future posts. Until then – Happy Growing!